By

John Townley

One

of the more elaborate – and intractable – rule sets

in

astrology is that of rulerships.

In order to determine the

strength/importance

of a planet, you must judge where it fits in a rigid hierarchy made up

when

there were only seven planets being considered. I take it with a

serious grain

of salt, and so should you. Here’s why:

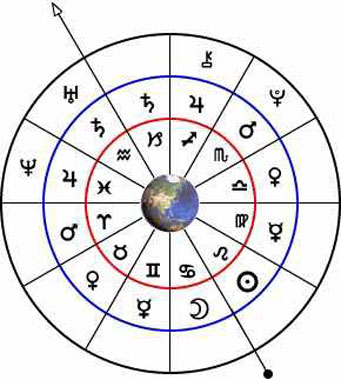

The

traditional way of treating rulerships goes back to a

concept of the universe in which our planetary system was not viewed as

one of

many, but the only one, the whole universe itself. In that system, the

seven visible

planets

were the lords of all activity and like humans had surrounding fiefdoms

over which

they ruled and had possession. Looked at that way, the chart becomes

like a set

of nation-states through which the planets travel, sometimes in their

own

kingdoms, sometimes crossing borders into kingdoms ruled by either

allies or

enemies, where they have less authority. And by totaling up who has the

most

and who has the least, and where it finally leads (as in a clever but

unhelpful,

tail-chasing “dispositor tree”) it could be

determined who the most powerful

magnate was, and who the weakest, who “ruled the

chart” and who owed what to

whom in the end and who didn’t. It is really astoundingly

anthropomorphic, and

tagged to a very specific historical political system.

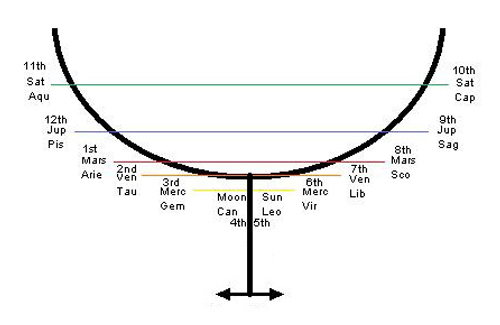

Original 7-planet

rulership tree was totally symmetrical, with inner

inconsistencies ignored in favor of overall structure.

Original 7-planet

rulership tree was totally symmetrical, with inner

inconsistencies ignored in favor of overall structure.In

a population of seven planets and twelve signs, it was

very neat and symmetrical, with Moon and Sun holding sway over

neighbors Cancer

and Leo, and then each planet in order of speed having two kingdoms on

either

side, progressing outward from the middle: speedy Mercury over Gemini

and

Virgo, sauntering Venus

over Taurus and Libra, determined Mars over Aries and Scorpio,

leisurely Jupiter over Pisces

and

Sagittarius, and deliberate Saturn tying up the opposite ends with

tangent

Aquarius and Capricorn.

Hierarchical and symmetrical, this was the celestial tree of life

– the whole

universe in its perfectly-formed completeness. (see illustration above)

But

in modern times, when politics below have proven a lot

more fluid and there are three or more extra heavenly bodies above to

take

into consideration, our understanding of rulerships has evolved. Now it

is

really more about general (and frequently overlapping) similarities

than any

fixed and circumspect set of influences. It’s rather like

taking a closer look

at modern nation-states and finding that they aren’t

totally homogeneous, but made up

of separate and often border-crossing ethnic minorities that may be

quite

different, despite being officially part of the same set. As our view

gets more

inclusively democratic, it also gets less definitive from moment to

moment.

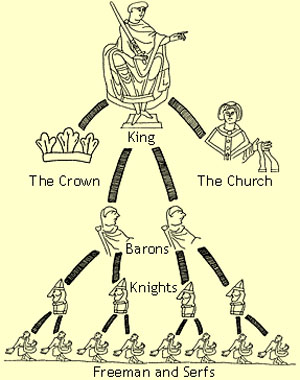

As new planets arose, the plan began

to lose its balance, and relevance, as did similar, rigid feudal social

structure tree.

Thus,

Mercury and its qualities of mental construction,

attention to specifics, and changeability seems to share qualities with

Gemini

(especially) and Virgo (perhaps less so). Mars clearly shares energy

and

aggressiveness with Aries, but not so much with more withdrawn

and

isolated (though powerful) Scorpio, while Pluto seems actually a bit

more

similar to that dark sign. Venus shares a love of opulence with Taurus

(but not its

propensity

for slowness) and an inclination to beauty and balance with Libra,

though not

Libra’s aggressive and applecart-upsetting inclinations.

Jupiter certainly has

the broad shoulders and inclusiveness of Sagittarius (though maybe not

so

rough-hewn), but doesn’t seem to have much in common with Pisces

at all, while

Neptune seems made to the task. Saturn and Capricorn seem a perfect

match, but

Aquarius though sometimes cold is far from conservative and stodgy, so

Uranus

would seem to share some of its more unusual and inventive side. Even

Sun and

Moon aren’t entirely perfectly matched to their signs, as the

Sun is constant

and reliable, whereas Leo doesn’t always hold up to that

standard, and

the Moon is far

too retreating and fickle for a season-dominating cardinal sign, though

it is

similar in other ways, such as sensitivity and empathy.

Comfort

is key

Still,

it’s important to consider whether a planet is

comfortable in a sign, as when it’s not, it is for all

practical purposes

partly debilitated. Saturn flounders in Pisces and Cancer, while being

utterly

overbearing in Aries, for instance. Neptune loses its essential staying

power

in Aries, while Uranus drowns in Pisces (where Mercury becomes

befuddled and

Mars loses focus), Jupiter in Capricorn is shorn of much of its

breadth, and so

on. But because all these discomfitures are partial, there’s

no hard and fast

rule, though the traditional set of rulerships, exaltations, and falls

sometimes does as well as

any. It

really depends on what side of the planet you are looking at and

whether that,

specifically, is helped or hurt by the sign it’s in. Even

neat subsets like

mutual reception don’t have consistent, or perhaps any,

meaning, depending on

where they fall. Mercury in Taurus and Venus in Gemini are in mutual

reception, but so is Mercury in Libra and Venus in Virgo. In the

first, Venus fares

better, in the second, Mercury does. The same sort of irregularity

applies for

all the rest, and more so when you throw in the outer planets.

Basically, it

means each is showing some uncomfortable and uncharacteristic qualities

of the

other, and is having to fight them.

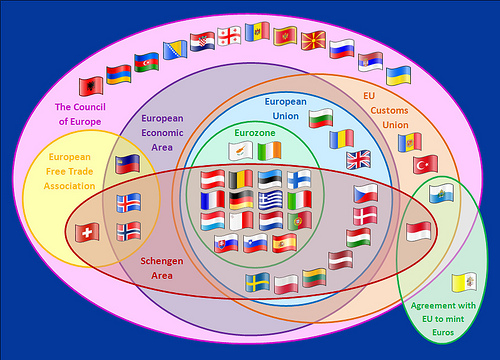

Rulerships these days are more like EU

states, partly homogenous, partly overlapping, depending on your

view...

So

in the end, it’s a new ball game as far as rulership

goes, and it might be better to use a variable weighting point system

(as Lilly

did), but one built to your own specifications and including whatever

your

favorite outer (and newer-discovered) planets/asteroids might be

– and then

adapt that to the particular situation you are looking at. Planets tied

by

easy, reinforcing aspects will make the most out of being in a

less-than-hospitable sign, whereas a hard aspect will simply reinforce

the discomfort of its position. Benefic or malefic transits and

progressions

will have

a similar, but more temporary, effect. And all of that is only as

relevant as the planet itself is to the particular issue you are

examining.

When

traditional astrologers (meaning Classical and

Renaissance) codified rulerships, they did it as a combination of

observed

similarities shoehorned into a formal structuring of the universe as

they thought

they knew

it. What we think we know about cosmology has greatly changed, but the

effects

of the planets have not…we understood it imperfectly then,

possibly equally-so

now – so although the context has changed, fortunately our

ability to

sense the

palpable reality has not, and that

is what we should be listening to.