It’s

been long enough since this original

history-documenting LP has been available – missing reprint

in

either cassette

or later CD formats – that it needs a brief twenty-first

century

historical

note itself. In the early 1970s, I was asked to sing and play on a

variety of

American history recordings in the run-up to the Bicentennial,

including album sets

for The National Geographic Society and Oscar Brand, who published a

book and several albums of

American Revolution period songs. Throughout, I found it peculiar that

almost all the material was political, as if singing about the war was

the only music on American lips at the time, which was very much not

the case.

So, after a year or so of poring over period music collections,

songbooks,

sailor’s companions, broadsheets, and contemporary musical

biographies at the

New York Public Library, Julliard, and elsewhere, I came up with a

collection

of what were actually the most commonly found songs in the historical

record of

the late Colonial and early post-Revolution periods. From these I

subtracted

the political songs (already recorded) and with the generous help and

support

of Gene Rosenthal at Adelphi Records,

went into the studio and recorded the

cream of the crop. They were the songs of love, drinking, hunting,

humor,

entertainment and even wry cultural commentary that

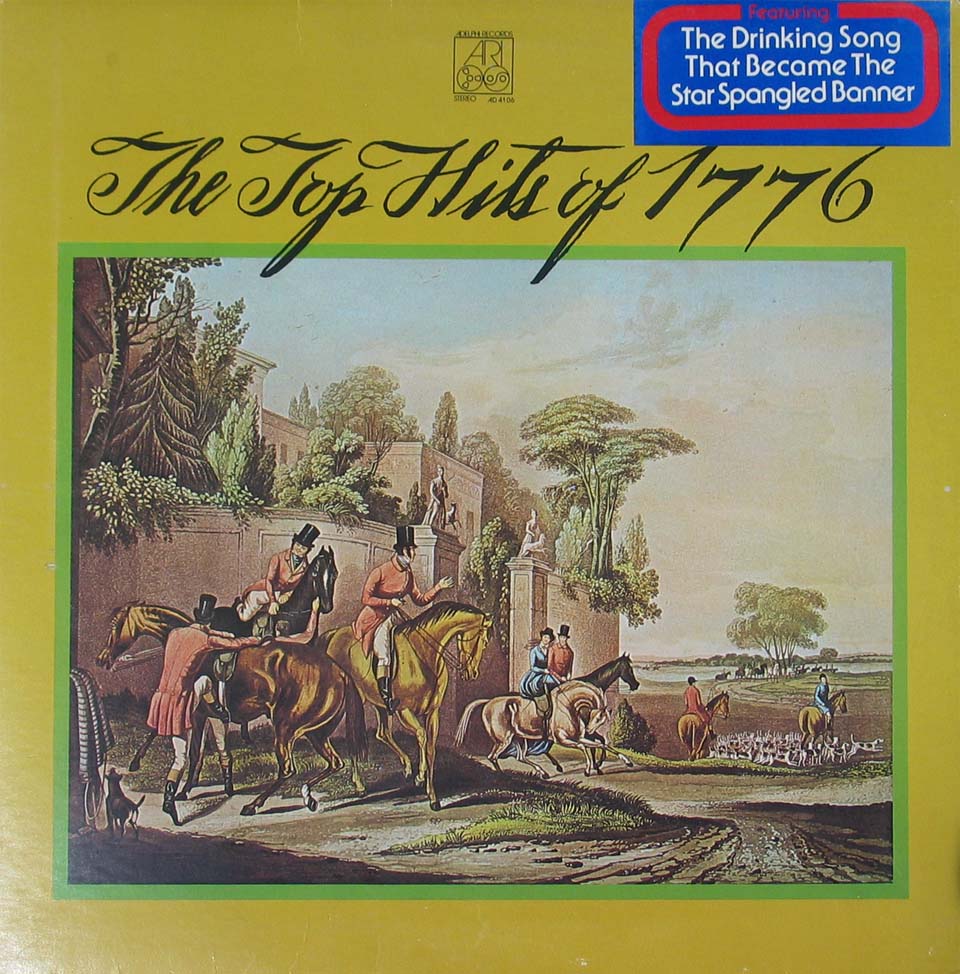

The reasons this effort has fallen into obscurity, without reprint, are both technical and economic. When the final mix was taken for disc mastering, it turned out the construction and electronics of the 8-track studio we used had conspired to hide serious distortion above about 12,000 Hz (it was a rock ‘n’ roll studio, nobody had noticed before), so we had to roll off everything above that level, turning it into a seriously lo-fi product – well, Martha Washington might have mastered it with one of her knitting needles, so perhaps there’s something vaguely historical there. Second, when release time for the spate of Bicentennial records came along in the spring of 1976, the press raised a terrific hue and cry about the “commercializing” of the event (in contrast to the mercantile bonanza of the 1876 Centennial), and the result was almost nobody made any money doing so. Even the most lavishly-funded and promoted productions lost money – indeed, this album was not even reviewed by a major newspaper, until it became the front-page pick of the New York Times art section exactly an entire year later.

So here it is, well-served by the .mp3 format so many years later. It contains many songs never before recorded, to this day. Indeed, Charles Dibdin’s jewel “The Hare Hunt” is no longer even available in his English sheet music collections and was fortunately saved by its reproduction in a contemporary American songster. The most obvious hit became “The Star Spangled Banner” for which we have also devoted an extra page here. Now to the original introduction, from the last century…

--

John Townley,

Sea

But what of earlier and simpler days before the rattle of Tin Pan Alley evolved into quadraphonic stereo? What songs rekindled memories of the birth struggles of a young nation for an aging George Washington or Thomas Jefferson? Or memories of mixing wenching with diplomacy for a greying, bespectacled Ben Franklin?

Although the 18th century is now generally better known for works by Mozart, Handel, and Haydn than for its top 40, far more money and energy was spent on producing and publishing the hit tunes of the day than was ever afforded to the works of the great masters.

Wherever good fellowship and jovial harmonizing was to be found—in the local tavern, on the popular musical stage, or in the drawing room—there was a constant turnover of new songs, ballads, and humorous ditties that rivals the output of today's monolithic record corporations.

The

center of the tangled

web of the 18th century

music business was

But as with our own century, out of the prodigious output of the pop

songwriters of the time comparatively few songs were memorable

enough to survive in the later song collections of the

1790's and early 1800's. During the war years,

very little music

was published in

At

the same time, musical periodicals

sprang up

chronicling all the latest hits, like

Songs at that time were performed by small groups of musicians singing and playing on the popular instruments of the time—the pianoforte, violin, cello, German flute, and guitar. The instruments were very like their modern counterparts except for the guitar, which was strung in six unison courses of two, more like the lute or folk 12-string guitar than the more modern 6-string Spanish guitar.

Full written instrumental arrangements were rare—most of the harmonization was left to the musicians with a basic pianoforte arrangement or simple bass line to refer to. Sometimes suggested flute or guitar harmonies would accompany a tune at the end of the manuscript, but often as not only the melody itself was included or simply the words alone if it was assumed everybody knew the tune.

The recorded performances here are a reflection of the fluid style of the day. Some parts were arranged, others simply made up on the spot by the performers, but all within the context of the popular harmony of the time. Likewise, the melodies themselves are the most common of the sometimes multiple variants to be found in different contemporary collections.

It

is a curious note on

popular music in general

that so few of these wonderful tunes

have

maintained their popularity into the 20th

century.

Only

"Drink To Me Only

With Thine Eyes" and

"To Anacreon In

Heaven"

(now

"The Star Spangled

Banner") are

still in current usage in the

But good songs have a way of resurfacing. The recent revival of long-forgotten renaissance and Elizabethan tunes is a good example. So perhaps the renewed interest in the history and politics of the 18th century will bring back its music as well—not just the formal classics but the love songs and drinking songs that suffused the lives of the people that built the age. Truly they are the songs that memories are made of—"Golden Oldies" from the childhood of a nation.

1.

To

Anacreon In Heaven — Written

in 1780 by John

Stafford Smith, this was the constitutional song of the Anacreontic

Society of

London, with words written by Ralph Tomlinson, an early

president of the Society. The

Society was a group

of mostly amateur musicians, with a sprinkling

of professionals, that met every two weeks at the

Crown and Anchor Tavern in the

To

Anacreon 1

in heav'n, where he sat in full glee,

A

few

sons of harmony sent a petition

That

he their inspirer and patron would be;

When

this answer arrived from the jolly old Grecian –

Voice,

fiddle, and flute, no

longer be mute,

I'll

lend

you my name and inspire

you to boot;

And besides, I'll instruct you like

me to entwine

The

myrtle of Venus with

Bacchus's vine.

Ye

songs of Anacreon, then, join hand in hand:

Preserve

unanimity, friendship, and love;

'Tis

yours to support what's so happily planned:

You've

the

sanction of

gods, and the fiat of Jove,

While

thus we agree, our toast let it be,

May

our club flourish happy, united, and free!

And

long may the sons of

Anacreon entwine

The

myrtle of Venus with

Bacchus's vine.

2.

The Lamplighter

—

Penned

by Charles Dibdin,

I'm jolly Dick, the

Lamplighter, they say the Sun's my dad;

And truly I believe it

sir, for I'm a pretty lad;

Father

and I the world delight and make it look so gay,

The difference is, I lights by night, and Father

lights by day.

For

I strange tricks and fancies spy folks never show the

Sun. Rogues,

owls,

and bats can't bear

the light I've heard your wise ones say;

And

so, d'ye mind, I sees

at night things never seen by day.

At night men lay aside all art as quite a useless task,

And

many a

face and many a heart

will then pull off the mask;

Each

formal

prude and holy wight will throw disguise away,

And sin it openly at night who sainted it all day.

His

darling hoard the miser views, misses from friends decamp,

And

many a statesman mischief brews to his country o'er his lamp.

So

Father and I, d'ye take me right, are just on the same lay;

I bare faced sinners light by night and he false saints by day.

3.

Down Among The

Dead Men

— This

first appeared

as an anonymous copperplate half-sheet

in

Here's

a health to the King, and a lasting peace

To

faction an end, to wealth increase;

Come

let's drink it while we have breath,

For

there's no drinking after

death,

And

he that will this health deny,

Cho:

Down among the dead men, down among the, dead men,

Down, down, down, down, down among

the dead men let him him lie.

Let

charming beauty's health go round,

In

whom celestial joys are found,

May

confusion still pursue

The

selfish woman-hating crew;

And

they that women's health deny, Cho:

In

smiling Bacchus' joys I'll roll,

Deny

no pleasure to my soul;

Let

Bacchus' health round briskly move,

For

Bacchus is a friend to Love,

And he that will this

health deny, Cho:

And

their united pleasure reign,

While

Bacchus' treasure crowns the board,

We'll

sing the joys that both afford;

And

they that won't with us comply, Cho:

4.

The Hare Hunt

— 18th

century writers were fond of allegories, and this one really takes the cake,

stretching a blast at the inhumanity of hare

hunting into a

cosmic justification for the ascendancy of evil. Another Dibdin jewel

from Castles In The Air,

first

performed at the Royal Polygraphic

Rooms in the

Since Zeph'rus first tasted the charms of coy Flora,

Sure nature ne'er beamed on so lovely a morn;

Ten

thousand

sweet birds court the smile of

And the woods loudly echo the sound of the horn.

Yet the morn's not so lovely, so brilliant, so gay

As our splendid appearance in gallant array,

When already mounted we number our forces

Enough

the wild boar and the tiger to scare;

Pity

fifty stout beings count dogs, men, and horses,

Should encounter such peril to kill one poor hare.

Little

wretch, they fate's hard, thou were gentle and blameless,

Yet

a

type of the world in thy fortune we see;

And

Virtue by monsters as cruel and shameless,

Poor,

defenceless and timid is humbled like thee.

See

vainly each path how she doubles and tries,

If

she 'scapes the hound Treachery, by Slander she dies,

To

o'ercome that meek fear for which men should respect her,

Every

art is employed, every sly, subtle snare,

Pity

those that were born to defend and protect her,

Should

hunt to her ruin, so timid a hare.

Thus

it fares with poor Merit, which mortals should cherish,

As

the heav'n gifted spark that illumines the mind;

As

reason's best honor left with it should perish,

Every

grace that perfection can lend to the mind.

Hark!

envy's pack opens, the grim lurcher Fear,

And

the mongrel Vexation skulk sly in the rear,

The

rest all rush on, at their head the whelp Slander,

The

fell mastiff Malice, the greyhound Despair,

Pity

beings best known by bright

truth and fair candour,

Should

hunt down, shame to manhood, so harmless a hare.

Their

sport's at an end, harsh reflection's beguiler,

To some thoughtless oblivion

their souls they resign,

The seducer takes pleasure to revenge the reviler,

The

hunter's oblivion more harmless is wine;

Thus

having destroyed every rational joy

That

can dignify reason they reason destroy,

And

yet not in vain is this lesson in spirit,

Ought of reverence for genius, respect for the fair,

So the tear of lost virtue and poor ruined merit

The sad spirits shall appease —

of the

innocent hare.

5. Banks Of The Dee — Written in 1775 by John Tait, an Edinburgh judge, upon the occasion of the departure of some friends to fight the Colonial rebels at the beginning of what came to be called the War of American Independence. According to Robert Burns, the tune is a slowed version of a popular Irish jig, but it certainly was intended to be played in the style of a Scots air or strathspey. The tune was very popular among American Tories and provoked many Rebel parodies.

'Twas

summer and softly the breezes were blowing,

And

sweetly the

nightingale sang from the tree.

At

the foot of a hill, where

the river was flowing,

I sat

myself down on the banks of the

Flow

on, lovely

They

banks, purest stream, shall be dear to me ever,

For

there I first

gained the affection and favor,

Of

Jaimie, the glory and pride of the

But

now he's gone from me and left me thus mourning,

To

quell the proud Rebels, for valiant is he,

But

ah! there's no hope of his speedy

returning,

To

wander again on the banks of the

He's

gone, hapless youth, o'er the rude roaring billows,

The

kindest, the

sweetest, of all his brave fellows,

And

left me to stray 'mongst these once-loved

willows,

The

loneliest lass on the banks of the

But time and my prayers may

perhaps yet restore him,

Blest

peace may restore my dear lover to me;

And

when he returns, with such care I'll watch

o'er him,

He

never shall leave the

sweet banks of the

The

The

lambs on its banks will again be seen playing,

Whilst

I, with my Jamie,

am carelessly straying,

And

tasting again all the sweets of the

6.

Lovely

Sweet

is the ship that under sail

Spreads

her white bosom to the gale;

Sweet,

ah sweet's

the flowing can;

Sweet

to poise the lab'ring oar

That

tugs us to our native shore,

When

the boatswain pipes the barge to man;

Sweet

sailing with a fav'ring breeze,

But oh much sweeter than all

these

The needle faithful to the

north,

To

show of constancy the

worth,

A

curious lesson teaches man;

The

needle time may rust, a squall

Capsize

the binnacle and

all;

Let the

seamanship do

all it can,

My

love in worth shall higher rise,

Nor

time shall rust, nor

squalls capsize

My faith and

truth to lovely

When in

the bilboes I was penned

For

serving of a worthless friend,

And

every creature from me ran;

No ship

performing quarantine

Was

ever so deserted seen.

None

hailed me, woman, child, nor man;

But

though false friendship's sails were furled,

Though

cut adrift by all the world,

I'd

all the world in lovely

I love

my duty, love my friend,

Love

truth and merit to defend,

To

moan their loss who hazard ran;

I love

to take an

honest part,

Love

beauty with a

spotless heart,

By

manners love to show the man,

To sail

through life by honour's breeze;

'Twas

all along of loving these

First

made me doat on lovely

1.

Batchelor's Hall

— Fox

hunting and the pleasures

of and particularly after the chase were the passion of the

18th century

gentleman on both sides of

the

To

Batchelor's Hall we

good fellows

invite,

To

partake of the

chase that makes up

our delight,

We have

spirits like

fire and of health such a stock

That

our pulse

strikes the seconds as

true as a clock,

Did you see us you'd swear, as we

mount with a grace,

That

Diana had

dubbed some new gods of

the chase:

Hark

away, hark away,

all Nature

looks gay,

And

Dick

Thickset came

mounted upon a

fine black,

A

better fleet

gelding ne'er hunter

did back;

Tom

Trig rode a

bay, full of mettle

and bone,

And

gayly Bob Buxom rode proud on a roan;

But the

horse of all

horses that rivalled the day

Was the

Squire's

Neck or nothing, and

that was a gray.

Let's drink to the joys of the next coming day.

Then

for hounds there was Nimble, so well that climbs

rocks,

And Cock-nose, a good one at scenting a fox;

Little

Plunge, like a mole, who will ferret and search,

And

beetle-browed Hawk's-eye, so dead at a lurch;

Young

Sly looks,

that scents the

strong breeze from the south,

And musical Echowell, with his deep mouth.

Hark away, etc.

Tis not likely you 'II easily find

such a stud;

And for hounds, our opinions with

thousands we 11 back

That

all

Thus

having

described you dogs,

horses, and crew,

Away we

set off,

for the fox is in

view.

Hark away, etc.

Sly

Reynard's brought

home, while the

horns sound a call,

And now you're all welcome to

Batchelor's Hall,

The

savory sirloin

grate full smoaks

on the board,

And

Bacchus pours

wine from his

favorite hoard;

Come on then, do honor to this jovial

place,

And enjoy the sweet pleasures that

spring from the chase.

Hark away, etc.

2. The Women All

Tell Me

— This

first appeared as

an anonymous copperplate half-sheet

in

The

women all tell me I'm false to my lass;

That

I quit my poor Chloe and stick to my glass:

But to you,

men of reason, my reasons I'll own;

And if you don't like

them, why leave them alone.

Although

I have left her, the truth I'll declare;

I

believe she was good,

and I'm sure she was fair:

But

goodness and charms in a bumper I see

That makes it as good and as charming as she.

Her

lilies and roses were just in their prime,

Yet

lilies and roses are conquered by time:

But,

in wine, from its age such benefit flows,

That we like it the better the older it grows.

She, too, might have

poisoned the joy of my life

With

nurses, and babies, and squalling, and strife:

But my

wine neither nurses nor babies can bring,

And a big-bellied bottle's a mighty good thing.

Perhaps,

like her sex, ever false to their word,

She

has left me to get an estate or a lord;

But

my bumpers (regarding nor titles nor pelf)

Will

stand by me when I can't stand by myself.

Then

let my dear Chloe no longer complain,

She's

rid of her lover, and I of my pain:

For

in wine, mighty wine, many comforts I

spy,

Should

you doubt

what I say, take a

bumper and try.

3.

John

Anderson, My Jo —

The

first and last verses, two simple

but touching stanzas by Robert

Burns, have inspired countless

tunes, dozens

of extra verses, and musical settings by composers

as diverse as Turnbull and Karl Maria Von

Weber. The

tune here is the most common, a

melody dating back to

Queen Elizabeth's Virginal

Book (1578)

and which may be an altered form

of the

earlier "I

Am The Duke of

John Anderson my jo, John,

when we were first acquaint,

Your looks

were like the raven, your bonnie brow was brent

But now you're turned bald,

John, your locks are like the snow,

My blessings on your frosty

brow,

John Anderson, my jo.

And

aye at church and market

I've kept you trim and neat;

There's some

folk say you're failing, John, but I scarce believe it's

so,

For

you're aye the same kind man to me, John Anderson, my jo.

John Anderson, my jo, John,

from year to year we've past,

And

soon that year must come, John, will bring us to out last;

But let that not

affright us, John, our hearts were ne'er our foe,

While in innocent delight we

lived, John Anderson, my jo.

John Anderson, my jo, John, we

climbed the hill

together,

And

many a happy

day, John, we've had

with one another,

Now we must totter down, John, but

hand in hand we'll go,

And

we'll sleep together at the foot, John

Anderson, my jo.

4.

The

Desponding Negro

— The

late 18th century

characterized the black man as a pathetic figure, torn from his

blessedly

primitive home

by rapacious slavers and then infected by all

the ills, both moral and physical, of his greedy

exploiters. Certainly here are the seeds of abolitionism,

already thriving in

With freedom stalks froth the vast desert exploring,

I was dragged from my hut and enchained as a slave,

In

a dark floating dungeon upon the salt wave.

Cho: Spare a halfpenny, spare a halfpenny,

Spare a halfpenny to a poor Negro.

Burst my chains, rushed on deck, with my eyeballs all

glaring,

When

the lightning's dread blast struck the inlets of day,

And its glorious bright beams shut

forever away.

The despoiler of man then his prospect thus losing.

Of gain by my sale, not a blind bargain choosing,

As my value compared with my keeping was light,

Had me dashed overboard in the dead of the night.

And but for a bark to Britannia's coast bound then,

All my cares by that plunge in the deep had been drowned then,

But by moonlight descryed, I was snatched from the wave,

And reluctantly robbed of a watery grave.

Torn

from home,

wife and children, and

wandering for bread

now,

While

seas roll between us which ne'er can be crossed,

And hope's distant glimmerings in darkness are

lost.

But of minds foul and fair

when the judge and the Ponderer

Shall

restore

light and rest to the

blind and the wanderer.

The

European's deep dye

may outrival the sloe,

And

the soul of an Ethiop prove white as

the snow.

5.

How Stands The

Glass Around?

— An

anonymous

For shame ye take no care, my boys,

How stands the glass around?

Let mirth and wine abound.

The trumpets sound,

The colors they are flying, boys,

To fight, kill, or wound,

May we still be found,

Content with our hard fate, my boys,

On the cold ground.

Why,

soldiers, why,

Should

we be melancholy,

boys?

Why,

soldiers, why?

Whose

business is to die!

What,

sighing? Fie!

Don't

fear, drink on, be jolly, boys!

'Tis

he, you or I!

Cold,

hot, wet, or dry,

We're

always bound to follow, boys,

And

scorn to fly!

I mean not to upbraid you, boys, —

'Tis but in vain,

For soldiers to complain:

Should next campaign

Send us to Him who made us, boys,

We 're free from pain!

But if we remain,

A bottle and kind landlady

Cure all again.

6.

Drink To Me Only

With Thine Eyes

— The

all-time

hit of the 18th century—hardly a songster

is without it. Still popular

today,

the words

date back to the 2nd

century Greek poet

Philostratus, whom

Ben

Johnson translated in his

poem "The

Drink

to me only with thine eyes and I will pledge with mine

Or leave a kiss within

in the cup and I'll not ask for wine

The

thirst that from the soul doth rise doth ask a drink divine,

But might I of

Jove's nectar sup, I would not change for thine.

I sent

thee late a roseate wreath, not so much honouring thee,

As giving it a hope that there it

could not withered be.

But

thou there thereon didst only breath and sent it back to me,

Since when it looks and tastes I swear not of itself, but

thee.

Many thanks to John Kilgore

for

transferring the original LP to .mp3

About Us

| Astro*Reports

| Readings

| John

| Susan

| Books

| Articles

| Astro*News/Views

| Astro*Links

| Music

| Site

Map