On the

subject of

astrology, the world is pretty much

divided into three camps: skeptics or religious zealots who know

nothing at all

about it

(but think they do) and loudly preach against it, consumers who only

know

their “sun

signs” and use it for fun, and practitioners who know

entirely

too little about

it and call themselves professionals. The result has been, for the last

couple

of hundred years, that this former “Mother of

Sciences” has

fallen onto hard

times, indeed.

But

there’s

something to it that just won’t quit –

something in the inner workings of human evolution that knows that God

doesn’t

play dice, a gut-level instinct that everything is somehow connected,

including

what’s on the earth and what’s in the sky, and that

survival depends upon

knowing it. The pursuit of just what those connections are and how to

frame

them is what’s bringing astrology back into vogue

worldwide and may

eventually restore her maternal status. To the horror of some and the

delight

of others, fervent interest in the stars, destiny, free will, chance,

and the

individual’s place among them is on the rise, big-time, but

so

far with more

heat than light on the subject. Everybody’s got a close-up

viewpoint to promote,

but few have a broad perspective on the matter.

Fortunately,

historian

Benson Bobrick has come along in

the nick of time (or, at the right, destined time, shall we say?) to

help

correct the problem. It’s time to see the forest instead of

the trees and

to study history so we don’t make the same mistakes yet

again.

And, as so often

happens, it is a work of newly-researched and refreshingly revisionist

history,

instead

of retrospective propaganda written by victors, that clarifies the

issue

and brilliantly illumines a formerly ill-lit stage.

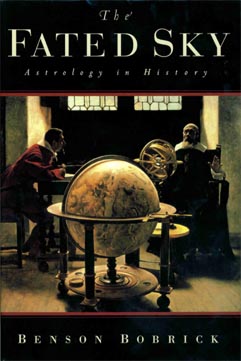

In The

Fated Sky,

Brobrick rises above the current

frays and their frayed arguments to present us with pure history, which

tells

the story better than any proponent of any particular approach possibly

could.

More important, he tells it from an inside, historical perspective

without the modernist “we-now-know-better” attitude

that

often plagues cultural

and scientific histories. He traces the evolution of astrology from the

inside

out, from its beginnings in Mesopotamia, through its golden Classical,

Arabic,

and Renaissance ages, into its sudden forcible rejection by both

science and

religion, right up to its currently hopeful but often clueless revival.

His

ever-detailed view is that of the astrologers themselves along with the

daily

users of their art – how and why they formulated what they

did,

and their

successes and failures in applying it to themselves and each other.

It’s

a long

journey, from there to here, and it’s a

well-told, entertaining, and eye-opening read all along the way.

Astrology buffs may already know that major public figures from the

Roman emperors

through the Medici to Ronald Reagan often consulted

the

stars. What

even

aficionados may not have heard are the amazing and marvelous details of

the

scheming and counter-scheming that went down on a daily basis between

astrologers and the royalty, politicians, generals, businessmen,

bishops and

popes who consulted them. On the scientific side, it is known to many

that some

of the most influential founders of modern science – Galileo,

Newton, Kepler,

Copernicus, Brahe, Boyle – knew something of astrology. But

few

realize how

totally wrapped up in it they often were, and how much it led their way

to the

discoveries they are most known for.

Further,

most people

today are only dimly aware of how steeped in astrological reference and

thinking European culture itself was, and still is. Most of us know of

a couple

of Shakespeare references to astrology, but in fact he made hundreds of

them --

often long, playful banters that assumed his audience to have an

intimate

knowledge of natal horoscopes and the particulars of their

interpretation. And

he was nothing out of the ordinary in this respect. Even the Church was

part of

the game, with elaborate arguments by St. Augustine and Aquinas that allowed

this Classical view of the universe

to fit in with the tenets of Christianity, or at least framed friendly

parts

for both to play. Not without reason was William Lilly's Christian

Astrology

the most important book of the 17th century on the subject.

The

fact is, astrology

was at the heart of the Western world-view - physically and spiritually

- right

up until well into the 18th century. It was the crowning technical and

philosophical endeavor that attempted to describe and make sense of the

universe,

inside and outside, from the cradle to the grave and beyond. All the

sciences

were within its purview, and vice versa, because life was considered to

be all

of a piece. It attracted the best and brightest minds in science,

mathematics,

literature, politics, and religion and in the process reached new

heights of

technical complexity, which only the best and brightest could generate

or even

keep track of. A glance at some of the generous quotes included from

contemporary chart

analysis would challenge the most astute modern astrologer, and they

are

impressively beyond arcane to the passing reader.

Sadly,

astrology's

brilliance was to become its undoing. As modern science evolved in the

17th and

18th centuries - founded in large part by thinkers who were astrologers

themselves - a new, separative concept of the world emerged, fueled by

the

economic gains provided by new technology. With it came a schism of

unbridgeable proportions between the spiritual and secular. The

foundations

laid by the likes of Newton sprouted a burgeoning world of mathematics

and

applied science that bankrolled a triumphant evolving secular society

and

backed the Church into a corner. By the middle of the 18th century,

secular and

spiritual sides pretty much agreed to part ways, with the generally

ineffable

and profound parts of life relegated to religion and the immediately

tangible

yet complex world awarded to science. Astrology, and the whole idea

that all

facets of existence are of necessity connected, was suddenly left

holding

the bag in

the middle and was soon excoriated by both sides. By the 19th century,

it was

considered quackery by one side, blasphemy by the other, and often

outlawed by

both. What had once been the most highly trained art of intellectuals

became a

lost litter of lore, scattered in the gutters of the uneducated and

gullible

masses who feasted on almanac prattlings, patent medicine, and

sun-sign

astrology.

In the

latter 20th

century,

astrology regained some small

semblance of its former stature, but only by adopting, and being

adopted by,

soft science like psychology and fringe religion like Theosophy. From

pop

sun-signs to “Jungian” astrology to “past

life”

sign and house regression, we are still a long way down from our former

heights and not doing much to reclimb

them. We are

trying rather badly to shoehorn pieces of a universal world-view into

our own

pet projections and cosmic conceits. Bobrick notes just that, and he

has little

patience for most modern practitioners. Yet, he is not without

hope,

observing that disciplines as far apart as weather forecasting and

agro-investment are including possible effects of the motions of Sun,

moon, and

planets, albeit tentatively.

Despite

its scope, the

book is individually

insightful and entertaining – it’s about how humans

have

used the art, after

all, in their own crazy ways. Suppose you’re emperor of Rome

and

it’s been predicted

that you face catastrophe ahead. Isn’t a logical approach to

instigate

disaster yourself, to pre-fulfill the prophecy and divert Fate's

intentions?

That’s what Nero thought, and so Rome burned. Ultimately, it

didn’t fix it for

him, but it did distract the public for a while. Toward this end of

history,

there’s Hitler. He actually held astrologers in contempt,

though

he had them

rounded up and shot, just in case. Rumors led the British to believe

otherwise,

however, so they secretly hired their own astrologer to

try to

predict the moves the Fuhrer would make based on what his (actually

non-existent) astrologers

were advising –

and with surprising success. The book abounds with such wonderful

contradictions – and also with tales of astonishingly

accurate

predictions

based solely

on cold charts -- where the astrologer doesn’t know

for

whom he’s

forecasting -- one of the phenomena that makes astrology uniquely

reliable

(sometimes) and bafflingly mysterious (always). Strange to say, ancient

astrologers were

much better at that than most are today, probably because their

methods

were more rigorous and their world itself had more limited options.

The

Fated Sky

doesn’t

officially take sides

on the validity of astrology, which is probably a wise move on the

author’s part, considering

that the subject faces, as he says, “head winds”

from all

points of the

compass. Early reviews of the book prove him right, as mainstream

critics somewhat

nervously

editorialize on the issue, implying either that it should not be taken

seriously (The

Washington Post) or that

it’s no crazier than neo-Darwinism

or string

theory (The New York Times).

The former senses that Bobrick may

be

dangerously

pro-astrology, and the latter cheers him on for it, each with doubtful

premises -- but all have applauded his thorough and

enlightening

inside approach to its history.

We

applaud it,

too, without reservation. If you

want to get a thorough sweep on Western

astrology and enjoy a

really good read in the process, go out and buy this book immediately.

There’s never been

anything

remotely close to it. And, for anyone intending to study the subject

with

professional aspirations, this should be required

reading

– after which,

at least half of the titles in the generous thirteen-page bibliography

should

come next.

Benson Bobrick

has been

called, in The New York Times

Book Review, “perhaps

one of the most interesting historians

writing in

America today.” He is the celebrated author of eight previous

books on various

subjects, ranging from the American Revolution to the translation of

the Bible

into English, and holds a doctorate in English and Comparative

Literature from

Columbia University. In 2002 he received the Literature Award of the

American

Academy of Arts and Letters.

Benson Bobrick

has been

called, in The New York Times

Book Review, “perhaps

one of the most interesting historians

writing in

America today.” He is the celebrated author of eight previous

books on various

subjects, ranging from the American Revolution to the translation of

the Bible

into English, and holds a doctorate in English and Comparative

Literature from

Columbia University. In 2002 he received the Literature Award of the

American

Academy of Arts and Letters.