|

Music in the Confederate

Navy

|

Presented at the 10th

Annual Mystic Seaport Museum Maritime Music Symposium, June 10, 1989

By

John Townley

Music

sung and played

on shipboard in the 19th century has been widely researched and written

about,

including many specialty areas such as songs of the whalers, fishing

songs,

naval ballads, and the like. Most,

although they may be more narrowly defined by a given segment of the

maritime

profession, cover a fairly broad expanse of time.

The

Navy of the Confederate

States Of America was only in existence for a little over four years

and in

toto numbered only about six

thousand men (as compared, say, to the

C.S.

Army's 600,000), so tracing music and songs in this narrow window might

seem

like a near impossibility. This

particular search is compounded by the fact that Southerners tended to

keep

written records of their activities less voluminously than their

cousins to the

North, being members of a culture with a strong oral but limited

written

tradition. In addition, much

of the

records that were kept during the war were destroyed in the devastation

that

marked its conclusion.

Nevertheless,

there

are enough references in books, journals, letters, and printed music to

give a

fairly suggestive picture of the music that accompanied the Southern

sailor to

war on the high seas and on the rivers and harbors of his home country. These,

in combination with a look at the

overall musical culture of the time, give a good idea of the music to

which the

CSN sailor was exposed or, in fact, penned himself and left for future

generations.

References

to music in

the CSN vary from a word or two dropped in passing to substantial words

of

praise for music aboard ship and the positive effect it had on the

sailors. A few on the

sketchy side

would be:

In

his journal,

Executive Officer of the C.S.S. Chattahoochie

docked at

Chattahoochie,

Florida on Feb. 18, 1863 notes that he heard the sailors on deck

singing a

song, and he quotes a verse:

"You

had better stay at

home with the girly you love so dear,

Than venture your

sweet life in a bold privateer."

He

also notes that the

ship had two fiddlers aboard -- one, the paymaster, was a classical

fiddler,

the other, the surgeon, played breakdowns.

Similar

notes in passing

are made in the journal of Assistant Surgeon Charles E. Lining on board

the

last CSN commerce raider C.S.S. Shenandoah:

"Monday,

May 1st, 1865, at sea lat. 33o01'20"N,

150o48'15"E....old Chew [5th Lt. Francis F. Chew] went fiddling in the

evening to the captain's while Lee [3rd Lt. Sidney Smith Lee] went to

work and

danced all his clothes off -- I don't know when I have laughed as much

as I did

at it." Later he observes:

"Saturday,

Oct. 21, 1865...At night Lee

got all the dancers among the men by the main hatch and by a little

whiskey set

them dancing until after nine o'clock."

Even

sketchier

conclusions may be made about another ship, the cruiser C.S.S. Georgia,

because

a reference by Capt. Raphael Semmes mentions Lt. R.T. Chapman aboard

the cruiser

C.S.S. Sumter as one who

"thrumbed

the light guitar, and sang delightful songs" and who, incidentally

subsequently served aboard the Georgia. Did

he bring his guitar?

Songs

were certainly

being sung aboard the cruiser C.S.S. Florida,

as a topman

aboard her

actually wrote a song of her exploits while under the command of Capt.

James

Newland Maffit, one of the most dashing and daredevil captains of the

CSN. The ballad

appears in The Civil War

In Song

and Story, 1889, credited anonymously and is set not quite as the text

suggests

to the "Red, White and Blue, (Southern edition)" -- there was such a

song, a parody on "Columbia, The Gem Of The Ocean" -- but to the tune

of the also very popular "Red, White, and Red." The

song survived in oral tradition into

this century and was collected in a version very close to the original

by

Joanna Colcord (thanks for that to Bob Webb, who found it in her

unpublished

papers a few years back). [Below, right, is the complete original text]

If

musical references

aboard some ships are scanty, one makes up for all the rest: the C.S.S.

Alabama. The

most

famous of all Southern raiders, her

depredations upon Northern shipping still hold the world's record for

all

commerce raiders today. Built in

Liverpool, England (like many other CSN ships) and commanded by captain

and

lawyer Raphael Semmes, she was more than a fearsome scourge to Yankee

shipping

-- she was one of the most musical naval ships of the 19th century, at

least

for which there is documentation.

Her

musical tale

begins before she made her hairbreadth escape from the Mersey River to

the

freedom of the open ocean, just hours ahead of an injunction that would

have

seized her. Union agents in

Liverpool

were collecting evidence to present to the British Crown that the

Confederacy

was building a warship in Britain in violation of that country's

neutrality

laws. American Consul

to Liverpool Thomas

Dudley had hired various spies to watch and infiltrate the operation,

among them seaman William Passmore. Passmore

reports his observations of June 26, 1862:

"Met

the seamen,

say thirty in number, on Saturday coming down Canning St. [in

Birkenhead] from

the ship from the ship, playing 'Dixie's Land' on a fife, concertina,

and

cornopeon [an early cornet] and they all took the 4:30 Woodside boat

for Liverpool. They still kept

playing

'Dixie's Land' on

board the ferry boat. Went up to one of

the men and asked him when he thought the ship would be going out. He

told me their bed clothes and bedding

were aboard and that the boatswain told those who intended to go in

her, to

hold themselves in readiness for early next week."

A

merry lot, indeed --

if all three instruments actually did make it aboard when she slipped

down the

Mersey on the 29th, then the Alabama had likely the only concertina in

the

Confederate Navy -- the instrument was almost unheard of in America

before the

Civil War, when it was brought to the North by Irish and German

immigrants

imported to help fight the war.

The

next reference to

music on the Alabama

is at her commissioning at Terceira in the

Azores

the following month, just after her tender had transferred her armament. On

Sunday, Aug. 24th, Semmes relates:

"A

curious

observer would also have seen a quartermaster standing by the English

colors,

which we were still wearing, a band of music on the quarter-deck, and a

gunner

(lock-string in hand) standing by the weather-bow gun.

All

these men had their eyes upon the reader

[Semmes reading the commission]; and when he had concluded, at a wave

of his

hand, the gun was fired, the change of flags took place, and the air

was rent

by a deafening cheer from officers and men; the

band at the same time, playing 'Dixie,' -- that

soul-stirring

national anthem of the new-born government."

No

mention is made of

what comprised this band, but fife, cornopeon and other brass were

common on

most ships of the period, along with various drums, and maybe in this

case a

concertina!

But

that was just for

official purposes. Once safely at

sea,

Semmes goes on to describe the routine on board ship and how he kept

the

sometimes idle hands of the crew busy:

"But

though I

took good care to see that my men had plenty of employment, it was not

all work

with them. They had their

pastimes and

pleasures, as well as labors. After the

duties of the day were over, they would generally assemble on the

forecastle,

and, with violin, and tambourine -- and I always kept them supplied

with these

and other instruments -- they would extemporize a ball-room, by moving

the

shot-racks, coils of rope, and other impediments, out of the way, and,

with

handkerchiefs tied around the waists of some of them, to indicate who

were to

be the ladies of the party, they would get up a dance with all due form

and

ceremony; the ladies, in particular, endeavoring to imitate all the

airs and

graces of the sex -- the only drawback being a little hoarseness of the

voice,

and now and then the use of an expletive, which would escape them when

something went wrong in the dance, and they forgot they had the aprons

on. The favorite

dancing-tunes were those

of

Wapping and Wide Water Street, and when I speak of the airs and graces,

I must

be understood to mean those rather demonstrative airs and graces, of

which Poll

and Peggy would be likely to be mistresses of...When song was the order

of the

evening, after the more ambitious of the amateurs had delivered

themselves of

their solos and cantatas,

the

entertainment generally wound up with

Dixie, when the whole

ship would be in

an uproar of enthusiasm, sometimes as many as a hundred voices joining

in the

chorus; the

unenthusiastic Englishman,

the stolid Dutchman, the mercurial Frenchman, the grave Spaniard, and

even the

serious Malayan, all joining in the inspiring refrain, -- "We'll live

and die

in dixie!" -- and astonishing old Neptune by the fervor and novelty of

their music.

Eight

o'clock was the

hour at which the night-watches were set, when, of course, all

merriment came

to an end. When the officer

of the deck

reported this hour to the captain, and was told by the latter, to 'make

it so,'

he put the trumpet to his mouth, and sang out in a loud voice, 'Strike

the bell

eight -- call the watch!' In an

instant, the most profound silence fell upon the late uproarious scene. The

witches did not disappear more

magically, in that famous revel of Tam O'Shanter, when Tam sang out,

'Well

dune, Cutty Sark!' than the sailors dispersed at this ominous voice of

authority. The violinist was

arrested

with half-drawn bow, the raconteur suddenly ceased his yarn in the most

interesting part of his story, and even the inspiring chorus of 'Dixie'

died a

premature death, upon the lips of the singers."

It

is often related

that the fiddler was a very important person aboard 19th century

sailing ships

-- if he knew his stuff. One San

Francisco story tells of six different captains vying for a

particularly fine

fiddler -- who woke up at sea one day in the hands of the winner! The Alabama

was no exception, and

Semmes takes note of the skilled musician by name who failed to return

to the

ship at Capetown, South Africa:

"I

was grieved to

find that our most serious loss among the deserters, was our Irish

fiddler. This fellow had

been

remarkably diligent, in his vocation, and had fiddled the crew over

half the

world. It was a pit to

lose him, now

that we were going over the other half. When

the evening's amusements began, Michael

Mahoney's vacant camp-stool

cast a gloom over the ship. There was

no one who could make his violin 'talk' like himself, and it was a long

time

before his place was supplied. Poor

Michael! we felt convinced

he had not

been untrue to us -- it was only a 'dhrop' too much of the 'crayture'

he had

taken.'

[The Alabama left more than her best

fiddler in Capetown. The ship was so well and memorably received there

that the townsfolk, and now celebrating tourists, to this day still

sing a toe-tapping Malay/Afrikaaner song "Darr Kom die Alibama" to this

day.]

Michael

Mahoney did

not have a suitable replacement until the ship reached Singapore, where

another

accomplished fiddler joined the lot, which brightened up things

considerably as

they proceeded into the Indian Ocean:

"And

then came on

the twilight, with its gray and purple blended, and with the twilight,

the

sounds of merriment on board the Alabama

-- for we had found a

successor

for Michael Mahoney, the Irish fiddler, and the usual evening dances

were being

held. We had now been

some time at sea,

since leaving Singapore; the 'jail had

been delivered,' the proper punishments administered, and Jack, having

forgotten both his offences, and their punishment, had again become a

'good

boy,' and was as full of fun as ever."

Delivered

from the

jail at this time was another musical hero of the ship, although

unrecognized

by Semmes, Frank Townsend. The Civil

War In Song And Story (1889)

quotes

a

ballad attributed to this Liverpool sailor about the battle between the

Alabama

and the Federal gunboat Hatteras,

in January of 1863 off the

coast of

Galveston, Texas. There the Alabama

lured a Federal ship off shore and sank it in a swift engagement of

thirteen

minutes, taking the prisoners afterward to Kingston, Jamaica. Townsend

immortalized the incident in a

song, with a tune unrecorded. By the

time the ship reached the Indian Ocean, however, Townsend appeared as a

ringleader of the crew's dissatisfaction with unmaterialized prize

money,

marked when the crew threw overboard cigars given out by Semmes from

the

captured ship Winged Racer. Townsend

was court-martialed and sentenced to thirty days in irons on bread and

water. Despite the

setback, he remained

loyal to the ship through her sinking at Cherbourg in June 1864.

The

officers joined in

the merriment and created their own as well on board the Alabama. Arthur

Sinclair, 5th Lieutenant aboard the

ship, relates numerous incidents in his narrative of the voyage Two

Years On

The Alabama. As

he relates:

"The

young

officers of the ship, with a view of passing the off hours pleasantly,

formed a

glee club; and as we had some charming voices among them, it was a real

treat to

both ward-room and forecastle. Weather

permitting, and no vessels to be boarded, at the approach of evening

the

audience gathers; the older officers occupy the 'private boxes' (to

wit,

campstools), the crew, the 'gallery' (topgallant-forecastle); and

cigars and

pipes being lighted by all who list, the programme of the evening is in

order. Songs

sentimental, songs

nautical, and, last but not least, songs national, delight the ears and

hearts

of all."

Later,

when some of

the officers are spun off to man a captured ship and turn it into

another CSN

cruiser, the Tuscaloosa,

they

are missed in the evening's musical gatherings:

"Evening

is now

on us, the Tuscaloosa

lost to us on the vast deep, and as we

gather

about the 'bridge,' and the glee-club forms its circle for song, we

first begin

to miss the bright, cheery face of our tenor, Mid Sinclair, and later

on, as

the night-watches pass, the strong, firm countenance of our late watch

relief,

Lieutenant Low."

Sinclair

has more to

report on the music on board in the persons of 3rd Lieutenant Joseph

Wilson and

marine Lieutenant Beckett Howell, whose instrument, like Semmes's

former

lieutenant Chapman, was the guitar. This

instrument is not mentioned often among

forecastle hands due to its

size and relative fragility, but 19th century sources often mention it

among

passengers and officers who had greater luggage space, as on land it

was the

portable instrument of choice. Howell

is mentioned just once, when he "hastily seeks his stateroom and the

consolation of his guitar," after a run-in with Wilson.

Joe's

talents, however, are praised:

"Joe

has vamosed

from the 'country' to have a quiet retired 'air' on his guitar all to

himself,

and is assaying a love-song, no doubt suggested by thoughts of his

inamorata

awaiting in far-away Florida his return with glory and prize-money. Joe

is not like his mocking-birds at home,

first-class as a songster; but he fingers his guitar well.

'Come

in, old fellow; I want to play an

accompaniment

for you!' And soon the

book, draughts,

chess, and the learned argument are dropped; and Joe's privacy is

utterly

wrecked. First one and

then another of

the glee-club take a turn at song; and the ward-room members of the

club

exhausted, the guitar is taken to the steerage and the music

continued..."

In

the Indian Ocean,

Sinclair recounts his own version of having a new fiddler and merriment

once

more in sway:

"Our

glee-club is

in the full tide of song; and even Semmes unbends from his dignity,

and, with

his camp-stool on the bridge and manila lit, smokes away the hours, and

listens

to the plantation songs interspersed with the more sentimental, and

winding up

with 'Dixie' and 'Bonny Blue Flag' just before the sound of eight

bells."

Music

accompanies the

Alabama right up to the end -- Joe Wilson's guitar, in fact, goes down

with the

ship in her battle with the U.S.S. Kearsarge

on June 19, 1864,

off

Cherbourg, France. As the ship

leaves

the French port to enter her final battle, the crew is advised to put

all their

valuables in a safe on shore in case she perishes in the fray:

"Joe

Wilson says

this latter gratuitous advice is well calculated to increase our

appetites, and

of little use to him, as all he has of value is his guitar, and that

won't go

in the iron safe, and besides he wants it to keep his spirits up. Howell

jumps to an idea, and wants to borrow

it at once as a bracer."

How

much music we know

was played on board CSN ships may well be a function of the extent of

their

fame and documentation on an individual basis. The

Alabama

was the most famous of all of

the South's ships and

certainly the most articulately documented in later books and memoirs. Had

cruisers and shoreside vessels of lesser

fame been favored with greater reason for their crews to write about

them, we

might know more about what they were singing and playing.

What

we may draw as general conclusions from Alabama's

experience probably only applies to the

CSN deepwater vessels

with international crews. The Alabama

had Southern officers but no American sailors (Semmes avoided them, for

loyalty

problems), so we are looking at a very international mix here. Other

cruisers which actually touched port

in the South like Florida

and Nashville,

might have

witnessed a

different musical situation.

When

one thinks of sea

songs, work shanties are usually the first that come to mind these days

-- so

what shanties were they singing during the Civil War, and what

developed from

it? The answer in

general is probably

all the common deepwater shanties that had been in vogue immediately

before. "Rolling Home,"

composed as a poem by British songwriter Charles Mackay aboard the

Cunard Liner Europa

in 1858 had probably already evolved into

the

famous

homeward-bound shanty. The well-known

capstan shanty "Roll, Alabama, Roll" possibly was already in use

before the end of the war. A really

good candidate, however, is "Bully In The Alley," the chorus of which

mentions Shinbone Alley, the heart of sailortown in St. Georges,

Bermuda. Bermuda was an

obscure port for

sailors

until the Civil War, when it became a boom town thanks to its critical

location

for one of three major bases for the blockade runners going into

Southern

ports. Common deck hands

could make

hundreds

of dollars in a single two-week round trip voyage to Charleston or

Wilmington,

landing ashore in Bermuda with untold wealth to squander in Jack's

inimitable

fashion. For four years,

things were

truly "Bully down in Shinbone Al," in a way they were never to be

again. After the war,

Bermuda went back

to the quiet coal station it was previously, so it is likely this song

originated from the blockade-running days of the Civil War. Another

sure candidate for a Bermuda-born

song is "Blind Isaac's Song," about the wreck of the blockade-runner Mary Celeste,

thanks to the probable Union sympathies of her pilot, who

ran her

on the rocks where he should have known better!

John

Townley is the founding

president of The Confederate Naval

Historical Society

|

|

|

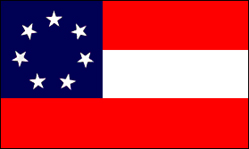

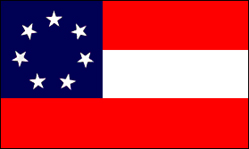

The Stars and

Bars

See

yonder bright

flag as it floats on the breeze,

It is feared by its

foes though it's young on the seas,

Like a bird on the

ocean 'tis met all alone,

But a deed of

dishonor it never has known.

In defending

its

rights much blood has been shed

As an emblem of

this see its borders all red,

And then look to

the center, the blue and the white,

The assurance our

cause it is true just and right.

Long may it

wave

o’er the ocean's dark breast,

Till the sun, moon,

and stars sink forever to rest,

May its gallant

defenders forever prove true,

With this wish, flag of freedom, I bid thee adieu.

--

from a

contemporary poetry collection

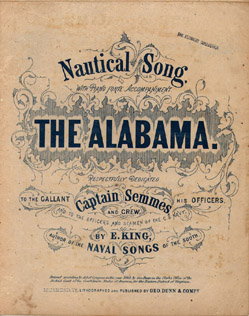

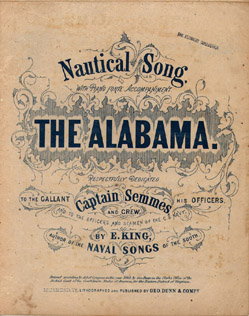

At sea and

land, the CSS Alabama

was the most sung-about

vessel of the Civil War. This song complete is available

here...

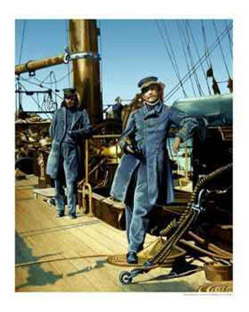

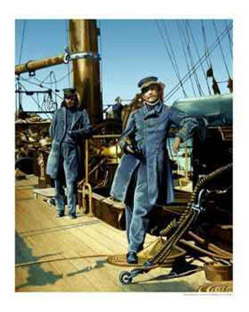

Alabama's

Capt. Raphael Semmes (shown with First Lieutenant Kell) kept a box of

musical instruments aboard for the use of the officers and crew.

CSS Florida's

exploits are

described below in song penned by one of her seamen.

“The Florida's

Cruise”

By a foretop-man of

the C.S.S. Florida

Air –

“Red, White, and

Blue” (Southern edition).

One evening, off

Mobile, the Yanks they all knew

That the wind from the

north'rd most bitterly blew;

They also all knew,

and they thought they were sure,

They'd block'd up the Florida,

safe and secure..

Cho:

Huzza! huzza, for the Florida's

crew;

We'll range with bold

Maffitt the world through and through.

Nine cruisers they

had, and they lay off the bar,

Their long line to seaward

extending so far,

And Preble he said as

he shut his eyes tight:

I'm sure they're all

hammock'd this bitter cold night.

Bold Maffitt

commanded, a man of great fame

He sail'd on the Dolphin,

you've heard of the same;

He called us all aft,

and these words he did say:

I'm, bound to run out

boys, up anchor, away!

Our hull was well

whitewash'd, our sails were all stow'd;

Our steam was chock

up, and the fresh wind it blow'd

As we crawl'd along,

by them, the Yanks gave a shout;

We dropp'd all our

canvas and open'd her out.

You'd have thought

them all mad, if you heard the curs'd racket

They made upon seeing

oar flash little packet;

Their boatswains did

pipe, and the blue lights did play,

And the great Drummond

light it turn'd night into day.

The Cuyler,

a

boat that's unrival'd for speed,

Quick let slip her

cables, and quickly indeed

She sought for to

catch us and keep us in play,

Till her larger

companions could got under way.

She chas'd and she

chased till at dawning of day

From her backers she

thought she was too far away

So she gave up the

chase and reported, no doubt,

That she'd sunk us and

turnt us somewhere there about.

So when we were out,

boys, all on the salt sea,

We brought the Estelle

to, right under our lee,

And burnt her and sunk

her with all her fine gear,

And straight sail'd

for Havana the bold privateer.

'Twas there we

recruited and took in some stores,

Then kiss'd the

senoras and sail'd from their shores,

And on leaving

their-waters, by way of a joke,

With two Yankee brigs,

boys, we made a great smoke.

Our hull was well

wash'd with the limestone so white,

Which sailors all know

is not quite Christianlike,

So to paint her all

shipshape we went to Green Keys

Where the Sonoma

came foaming, the Rebel to seize.

We put on all sail and

up steam right away,

And for forty-eight

hours she made us some play,

When our coal being

dusty, and choking the flue,

Our steam it slack'd

down, and nearer she drew.

Oh, ho! cried our

captain, I see what's your game!

Clear away the stern

pivot, the Bulldog

by name,

And two smaller dogs

to keep him companie,

For very sharp teeth

have those dogs of the sea.

The Sonoma

came

up until nearly in range,

When her engines gave

out! -- now wasn't that strange?

--I don't know the

truth, but it's my firm belief

She didn't like the

looks of the Florida's teeth.

She gave up the chase

and returned to Key West,

And told her flag

captain that she done her best;

But the story went

round; and it grew rather strong,

And the public

acknowledg'd that something was wrong.

We went on a-cruising

and soon did espy

A fine, lofty clipper,

bound home from Shanghai;

We burnt her and sunk

her in the midst of the sea,

And drunk to Old Jeff

in the best of Bohea!

We next found a ship

with a quakerish name:

A wolf in sheep's

clothing oft plays a deep game --

For the hold of that

beautiful, mild, peaceful Star

Was full of saltpetre,

to make powder for war.

Of course the best

nature could never stand that,

Saltpetre for Boston's

a little too fat,

So we burned her and

sunk her, she made a grand blaze,

She's a star now gone

down, and we've put out her rays.

We next took a

schooner well-laden'd with bread;

What the devil got

into Old Uncle Abe's head?

To send us such

biscuit is such a fine thing,

It sets us all

laughing as we sit and sing:

We next took the Lapwing,

right stuff in her hold,

And that was black

diamonds that people call coal;

With that in our

bunkers we'll tell Uncle Sam,

That we think his

gunboats are not worth a damn.

The Mary

Jane

Colcord to Cape Town was bound,

We bade her heave to

though and swing her yards round,

And to Davy Jones'

locker without more delay

We set her afire, and

so sailed on our way.

-- From The

Civil War In Song And Story,

1879

CSS

Florida's

and CSS Alabama

cross paths in a painting,

though they never did in life.

Roll Alabama Roll

-- contemporary

capstan shanty

When the Alabama's

keel was laid

Roll,

Alabama, Roll

It

was laid in the yards of Jonathan Laird,

O

roll, Alabama,

roll

It was laid in

the

yard of Jonathan Laird

It was in the

town of

Birkenhead.

Down Mersey way she sailed

then

She was Liverpool-fitted with guns and men.

Down Mersey way she sailed

forth

To destroy the commerce of the North.

To Cherbourg port she sailed

one day

To collect her share of prize money.

And many a sailor met his doom

When the Yankee Kearsage

hove

in view.

A shot from the forward pivot

that day

Blew the Alabama's

stern away.

Off the three mile limit in

sixty-four

The Alabama

sank to the

ocean floor.

Was

the fiddler in CSS Palmetto State's

minstrel show the same Lt. Chew who regaled officers of CSS Shenandoah?

CSS Shenandoah

sails into the Mersey,

the last to lower the flag, in November 1962

|