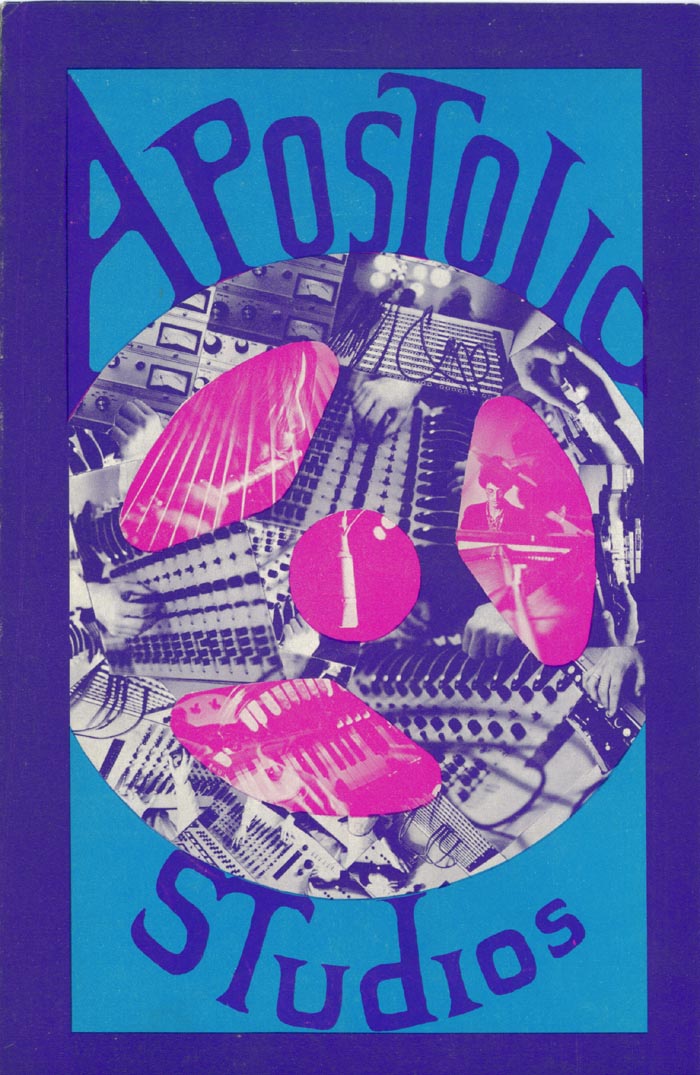

Like the

cover of its brochure, Apostolic was an eclectic collage of music and

technology...

(A personal reminiscence

originally

published

in EQ

Magazine, 1998 as

"Laid-Back Multitrack:

The Downtown Birth of Modern Recording Studio Style")

Part I: A Place To Create

By

John Townley, founder

I

cannot go into a

recording studio these days without feeling a deep mixture of

satisfaction and

regret. Satisfaction,

because I know

I'll find the kind of equipment I need and the atmosphere of creativity

I want

to get the job done. Regret, that you

can't copyright an idea -- otherwise, I'd be rich, since the marriage

of

equipment

and atmosphere is something I invented way back when it all started...

And

since you've

doubtless never even heard of me, I'd better justify that claim -- but

first, a

flashback to when I was recording for Columbia back in '65, with a New

York

group called the Magicians, an act that almost made it, but...well, our

producer Charlie Koppelman had fatter fishes to fry, as did Columbia's

Goddard

Lieberson. Roy Halee was our

engineer

(producer/engineer for Simon and Garfunkel), and with the exception of

his

incredible talent, recording was about as unpleasant a chore as you

could

imagine. Not only was it

user-unfriendly, it was ludicrous. The

uptown Columbia studio itself was hideously brightly lit, so every

smudge on

the dirty, pegboard-lined walls stood out and erased whatever chemistry

you might

have prepared on the way in. Definitely

several tokes under the line...the very foundation for justifiable

musician

paranoia, because...

...there

were only

eight tracks to work with (you wonder how the Beatles survived so well

on that

-- lots of money/time helped), and there was no separate cue system for

overdubbing (honest!), so you listened to whatever mix the engineer

needed to

do his trip. And, it was a

union shop,

with three separate engineers, each with discrete responsibilities with

which

no one, but no one, was allowed to interfere. So,

doing a take was kind of like a WWII submarine

movie: "Take one!" cries

Roy. "Tape is

rolling," informs the man

in charge of starting the 8-track, in an entirely separate room. "Echo

on!" finishes the third in a

yet more distant room, punching on the 2-track tape delay.

After

that, you got to start playing...all

that was missing was the wait to hear if the torpedo had found its

mark...

Mixing

was equally as

crazy, as you still had all three to deal with, and you were never -- I

mean

NEVER -- allowed to touch a fader, lest you get your fingers slapped. You

had to tell each engineer what you

wanted and hope he understood. All the

major record company studios were like that, and independent studios

weren't much

different.

By the

fall of '66,

I'd had it with group, recording, and first marriage, so I took some

money from

a small inheritance and idealistically launched out to CHANGE IT ALL... What

was amazing -- I did!

First,

I picked a

downtown location, in the Village, as that's where all the musicians

were. Be where you're

comfortable. After all, only

the execs were uptown. It was a loft

building on 10th St. near

Broadway, with a hand-operated freight elevator its primary access, one

where the

elevator had no walls and worked by pulling a cable to make it start

and stop.

That was a golden opening opportunity -- our artist/"elevator man"

Nicky Osborn soon had the entire darkened six-story shaft detailed in

black-light psychedelic murals, and his personal welcome in full Viking

costume

definitely made a serious start on the way up. Way

up. We often

wondered what

the clients of the very-tolerant baseball cap sales company on the 6th

floor

thought of it....

The

rest of the studio

followed suit, with totally controllable theater lighting throughout,

so

whatever the state of your insides, you could make the environment

match. "No smoking"

signs in every

respect were a thing of the future, indeed...

The

equipment matched

the decor, user-friendly to the possible max. I

insisted on the first independent cue system on

any mixing console,

ever (built by Lou Lindauer, his Automated Processes' opening gambit,

who

brilliantly nursed us through our demanding technology changes). And,

of course more tracks (how quickly you

run out at only eight) -- we went to twelve because that was as many as

Scully

could crowd onto a relatively-editable one-inch tape transport in this

first-of-a-kind machine they built to our specs. And

faders, instead of pots (goodbye '50s sci-fi flicks), also a

first, and the new-fangled solenoids...best of all, everyone could

touch them

all, no union, except don't spill your Coke on the board!

All

that, and teenage whiz engineer Tony

Bongiovi (later, brother/producer of Jon Bonjovi) were enough to launch

us into

the ozone.

When

we opened in the

spring of '67, everyone in "the biz" said we were crazy:

no

one would come downtown, nobody needed

twelve tracks, and our whole style was VERY un-businesslike...our name

was

Apostolic Studios, after our twelve tracks and unabashedly spiritual

(though

not particularly Christian) tilt, and clearly we were nuts.

Well,

inside three

months we were booked solid. The

Critters, Spanky And Our Gang, the Serendipity Singers, the

Fugs,

Rhinocerous, The Silver Apples, Kenny Rogers and the First Edition,

Alan Ginsberg, the Grateful Dead and

most of all

Frank

Zappa and the Mothers Of Invention found the qualities of user-friendly

tech

and musician-friendly ambience to be just what the doctor ordered. Six

months after that, Gary Kellgren, who

had made an early reconnaissance visit to Apostolic, opened Record

Plant with

an identical 12-track Scully and similar board and ambience, and

shortly

thereafter Jimi Hendrix built Electric Ladyland downtown on 8th St.,

just

blocks away. Alas, personally

among

them, I alone (though no longer my studio) remain...

Flushed

with success,

Apostolic went on to open another 12-track operation (Pacific High in

San

Francisco, the first on the West Coast), to become a

record/publishing/management company (Larry Coryell, Jim Pepper, and

the like),

and to see our "Witchi-Tai-To" Cherokee trance song become a national

favorite, with Wall Street backers for a public offering.

As

a studio, we continued to keep up,

providing clients not only with every kind of strange

international/historical

instrument they might want to play (want a kan,

a del ruba,

a viola

d'amore, a rauschpfeife?...no

problem), they even got the

free

services of world-class astrologer Al Morrison, who shared one of our

floors. The latter was a

good thing, as

Al provided me with a second career when the majors ate us up at the

beginning

of the '70s and I found myself a quite useless music biz innovator

alone on the

street.

But

although we were

doomed to meet our demise at the hands of over-expansion, competition,

and a

business world which utterly co-opted our concepts, the studio retains

memories that

are unique to its origins. The day the

brother of a very famous blues/rock guitarist took microgram-inspired

wings

from our window, falling face-down to the roof two floors below

-- leaving a

tar-paper "angel" on the roof, he proceeded unscathed two more floors

to the back garden. The boa

constrictor

entwined in the bidet (and afterwards, the water cooler) that could not

be

smoked out (we succumbed before it did...). Generations

of Mothers trooping in and out for

"Lumpy Gravy"

and "Uncle Meat" sessions...and in the process recreating the then-rare

"flange" effect, employed by Zappa and our engineers at Apostolic

using a reverse-phased, slightly trailing variable-speed controlled

2-track

Scully. About

the

"flange," engineer John Kilgore remarks, "I first heard it on Toni

Fisher's 'The Big

Hurt' in 1959. then on 'Itchykoo Park' by the Small Faces in early '67,

and

on Hendrix's second record released in '67. I remember Kunc and I

bashing our

brains out trying to figure out how it was done. Finally,

Dick called up

Gary Kellgren and asked him how point blank. Gary, bless his heart,

told him."

For more on that one, see: here

and here.

There were a lot of firsts and, mainly, a

family where creativity and technology finally worked hand-in-hand.

Now

it all seems like

old hat. These days, you can get lots more than this, by a landslide,

in any

pro recording studio and many home installations. But,

hard as it is to believe, it wasn't always that way -- there

was a time when the design of the recording studio was utterly

business-driven,

not musician-driven, when creation in front of a mike was not exactly

natural

childbirth. In 1967, all that

changed,

forever -- and I am proud and thankful to be able to say that Apostolic

and its

engineers, producers, and musicians -- achieved that in, essentially,

one

take...

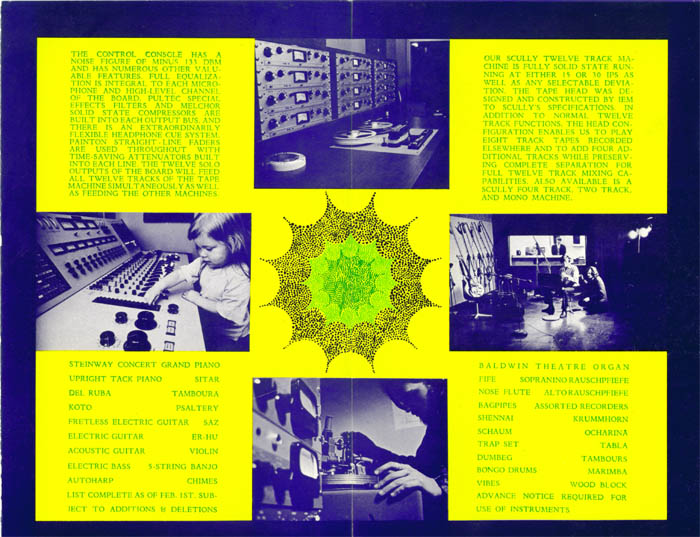

The

studio featured musician-friendly, state-of-the-art electronics,

atmosphere, unusual instruments.

Part II: Historic Hardware

In

Soft Focus...

by

Richard Kunc,

former Apostolic Studios engineer

I

recall the API console as a sea of

blue Formica, a wondrous machine praised

by Frank Zappa, with sparkling new

arc-shaped British Painton

faders. Sort of "proto-faders," actually, the Painton controlled a

linear series of many individual make-and-break contacts. On very quiet

passages you could actually hear the tiny "bip-bip-bip" as it went

from contact to contact.

Each

input position had rudimentary

equalization available, but it amounted to little more than glorified

bass and

treble controls. We had a pair of Lang equalizers mounted externally to

help

the cause. The input positions were normalled to their corresponding

tape

tracks, but you could reassign any input to any tape track via the

patchbay.

For mixing you could also assign each input position to either left,

center, or

right. These were hard switch selections. There were no pan pots on the

input

positions. You could patch into the console's two independent pan pots

but that

was it.

Three

Melchor compressors did give

us a smidgen of ceiling control in extreme cases. They were better

known for

their pronounced and dramatic "breathing" effects in which the

momentarily suppressed background sound comes rushing back up in volume

after

the peak has passed. Also external to

the console was a very fast (for its day) limiter that used a light

source

coupled to an optical detector to do its work.

The

prototype Scully twelve-track

machine used one-inch tape. It had twelve sets of their normal

full-size

rack-mounted electronics, the ones they put in their mono and two track

machines -- imagine twelve of those babies, each one with a complete

set of

knobs and full-size meter! It was just huge -- but it worked. One

problem with the machine was bleed-over

while recording on adjacent tracks, so we'd record on odd-numbered

tracks

during the first pass, and then overdub in between the initial tracks

from then

on.

The

machine had one neat trick,

though. You could take a one-inch tape with eight tracks recorded on it

by an

eight-track machine, put it on our twelve-track machine, and add four

more

tracks! You ended up with

twelve very

mixable tracks, all of which still had very acceptable signal to noise

ratios,

and it made us completely compatible with other 8-track studios.

The

primary "echo chamber"

was one of those "state-of-the-art" EMT vibrating steel plate deals.

Inside a huge wooden case a sort of loudspeaker was attached to one

corner of a

metal plate that must have measured maybe four feet by eight feet. When

you fed

a signal to this "speaker" it sent waves through the plate, sort of

like ripples on a pond. A transducer at the opposite corner picked up

these

waves, equalized them, and sent them back as echo.

There

were also some experiments with live speakers

and

microphones in the stairwell of Apostolic's ancient building, much to

the

dismay of the residents of the other floors, and whose complaints

effectively

squelched our efforts.

What

gave the console its

saving-grace versatility was its extremely comprehensive patchbay. It

was the

old tip-ring-sleeve variety, left over from telephone company

technology,

though more than one unrepeatable take was destroyed by some bit of

studio dust

that got in there...

And

for microphones - a few Neumann

U-67 condenser mics with their accompanying power supplies, a few

borrowed

Sennheiser ribbon mics, a smattering of assorted decent dynamics,

including

those warm and indestructible cone-headed D-202s, and a motley gang of

one-of-a-kind items including an indestructible Altec "salt shaker"

routinely used for drums and a giant, mellow vintage RCA mike that must

have

recorded Bing Crosby or the Andrews Sisters in its youth.

In

the control room were large

hard-edged Altec monitor speakers, behind the console. Took a bit of

getting

used to. Plus the favored

(by us)

KLH-6s up front that blew out all the time when the clients said

"louder," not to mention delightful Boze clones built by Gus Andrews,

our first reggae recording artist.

Apostolic

was a real Viking ship, a

gutsy voyage into the uncharted depths of new toys and new ideas from

which

came some of the cleanest recordings of that era. I'd

give a lot to sit again at that console and look through the

glass at those original Mothers of Invention.

Rest

well, Apostolic.

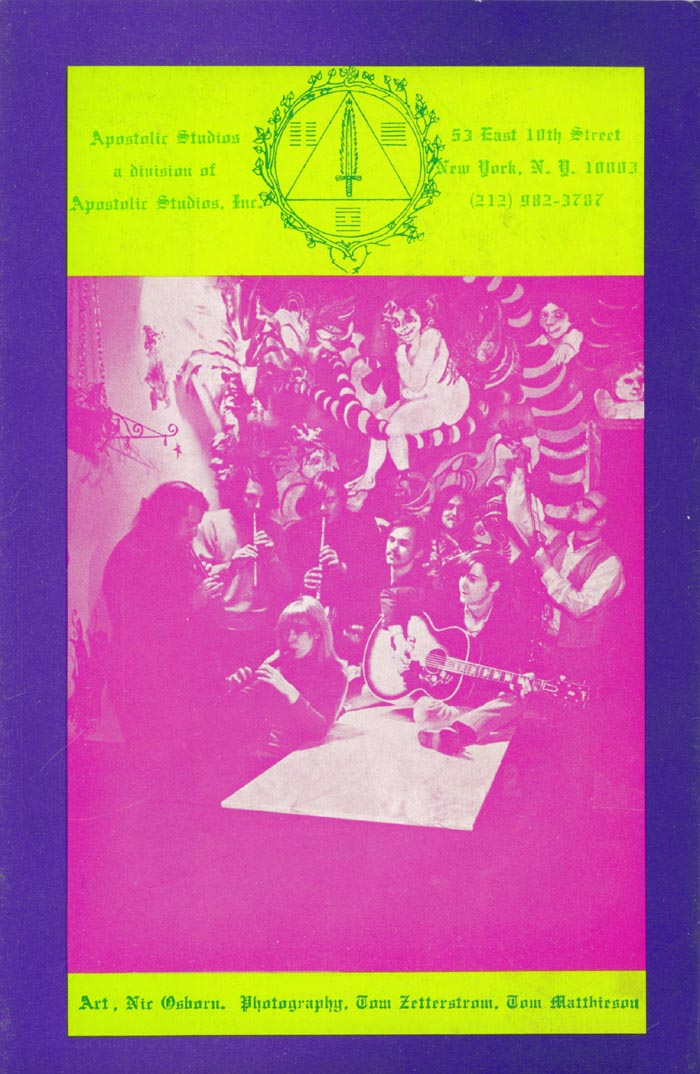

Some of

Apostolic's festive crew, at

reception

desk, 1967: Matthew Hoffman, Danny Weiss, John Kilgore, Randy

Rand, Nic Osborn, Richard Kunc

(top, l-r).

Monica Boscia, John Townley (below, seated).

|